by John Blackmore

One of the most exciting things about the Victorian Literary Languages project – aside from the strong case it sets out for a multilingual Four Nations Victorian Studies – is that it shines a spotlight on non-standard English in writing emanating from different corners of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales during the nineteenth century.

Writers were attracted to non-standard English variants for a number of reasons. For some poets and novelists, it could be used to help evoke a character’s (or writer’s) associations with a specific geographical area and its culture. For other writers, non-standard English became an object of study; the vocabularies, linguistic features and histories of regional dialects were the focus of philological investigation that sought to categorise and chronicle language use in a given space over time. In some cases, writers combined creative and scholarly approaches to non-standard English.

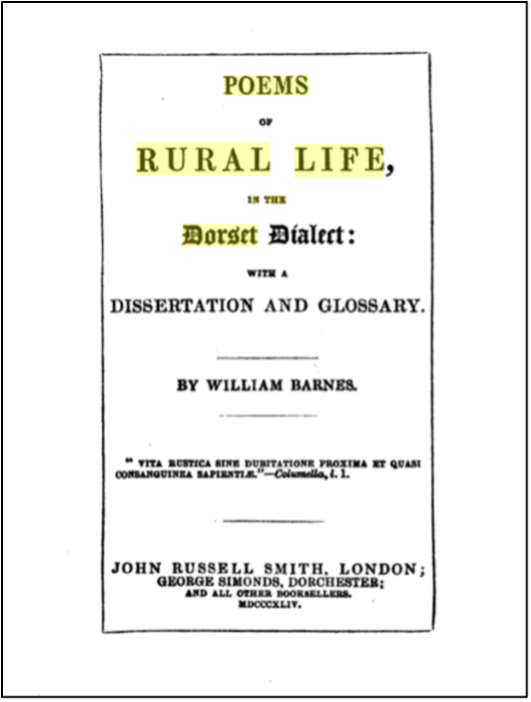

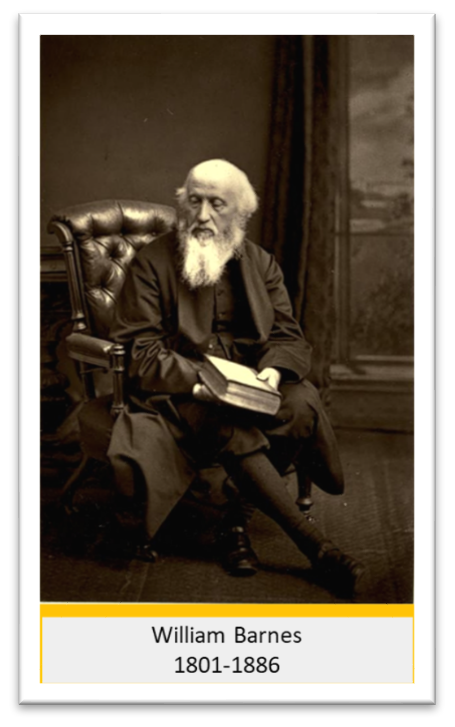

William Barnes (1801-1886) is best-known today as a nineteenth-century Dorset Dialect Poet. His first collection, Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect (1844), was published with a glossary and dissertation which, as well as being a useful resource to readers not familiar with the dialect, also gives an indication that Barnes’s poetry was informed not just by personal, local attachment, but by philological scholarship, too. On one hand, Barnes’s dialect poetry might be read as some sort of small-scale protest against the spread of standard ‘Book English’ across Britain’s regions in the mid-nineteenth century (3). On the other hand, however, the Anglo-Saxon resonances Barnes uses to authenticate his codification of Dorset speech also aligns his dialect system with the era’s nation-building philological projects that sought to trace the roots of the English Language back to the time of King Alfred (3).

Today, Barnes’s affinity with the people and places of his native Dorset is, arguably, one of his defining characteristics. The tensions in Barnes’s separate-but-related pursuits of poetry and philology have been somewhat lost as his dialect poems received more attention and praise for their intimate portrayal of rural life.

But Barnes’s interests in non-standard English, particularly his scholarly, philological interests, were not limited to Dorset.

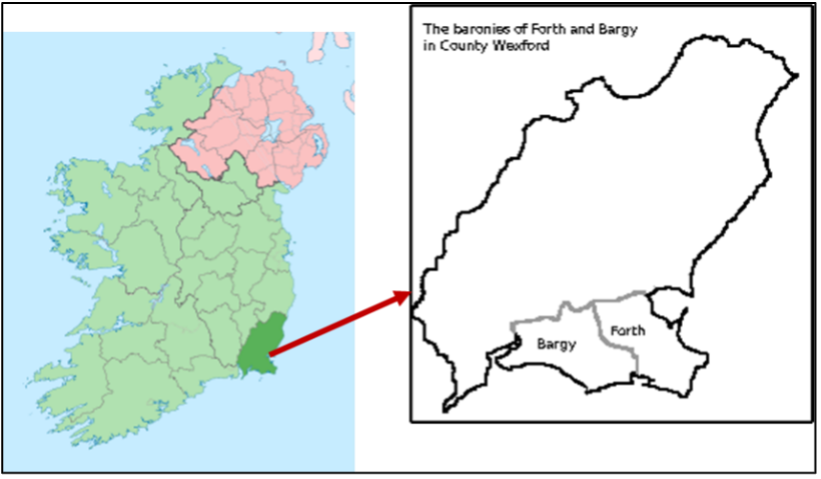

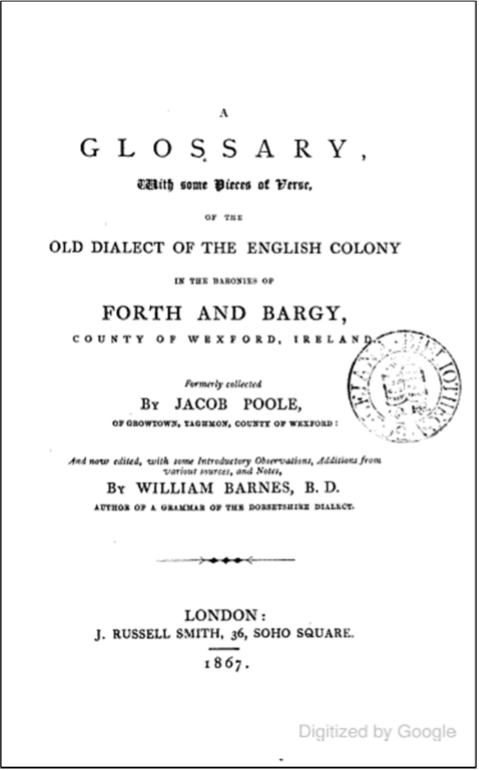

One of the more unusual publications to bear Barnes’s name is an edited volume containing a glossary and poetry in the Yola language: a non-standard English variant spoken by inhabitants of County Wexford in the south-east of Ireland between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries. The 1400-word glossary and nine poems were originally compiled by Wexford resident Jacob Poole (1774-1827). To Poole’s original hand-written manuscript, Barnes added an editorial, expanded the glossary and added other source material and appendices and published the work under the title A Glossary with Some Pieces of Verse of the Old Dialect of the English Colony in the Baronies of Forth and Bargy, County Wexford, Ireland (1867).

There are several factors that might have accounted for Barnes’s interest in Yola. One reason might have been that, like the dialect of Dorset, the language was contained to a relatively small but distinct area. It was unique to the districts of Forth and Bargy in South Wexford and seems to have resisted some of the effects of Gaelicisation and the advance of Modern English up until the eighteenth century. Another reason might have been that the language was tantalizingly just out of the grasp of nineteenth-century philologists. While Yola had been codified in the form of song lyrics, poetry, hymns, glossaries and accounts by antiquarians from as far back as the sixteenth century, it was thought to have stopped being used by a community of speakers in the mid-nineteenth century – no more than two decades before Barnes published his edited volume of Poole’s Glossary. But the language’s supposed links to the arrival of Anglo-Norman, Flemish and Welsh settlers in the twelfth century provides a further interest for Barnes’s interest in Yola. Not only did this version of history allow Barnes to read for Anglo-Saxon roots in Yola, but it afforded him opportunities to draw associations between the Yola and his own Dorset dialect.

As a figure renowned for his championing of an underrepresented regional dialect and culture, and one with a deep-rooted sense of place and community, Barnes would seem a safe and sensitive choice as an editor of Poole’s Glossary of Yola words and verse. But the editorial decisions made by Barnes in this book cast a very different light on his position as a spokesperson for working-class, non-standard English speakers. His choice of supporting texts and appendices to embellish Poole’s Glossary also invites us to reconsider his stance on the role of language in colonial projects.

Three of these historical sources stand out, on account of their Anglocentric views and perspectives. They are a ‘Congratulatory Address’ written and spoken in Yola by a Mr Edmund Hore in Yola on the occasion of a visit to Wexford by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1836; an extract from Richard Stanyhurst’s (1547-1618) account of Wexford originally included in Holinshed’s Chronicles in 1577; and a scholarly paper on Yola by English military surveyor General Charles Vallancey (1731-1812), which was read before the Royal Irish Academy in 1788.

The way Barnes uses these sources to contextualise and embellish Poole’s Glossary stresses Wexford’s status (and that of the island of Ireland more generally) as a colonial territory governed from London. While the 1801 Act of Union formalised this arrangement, that some of Barnes’s most important source texts predate this indicates how the suppression of Irish culture and English occupation of Ireland had been normalised long before the nineteenth century.

What is surprising, however, is that unlike in Poems of Rural Life (1844), where Barnes draws attention to the intimate connections between Dorset language, Dorset places and Dorset communities and juxtaposes these with the threats posed to them by Standard English, there is no sensitivity or empathy for how these same processes had long been underway in Ireland. Ireland and the Irish are not really in focus in the Glossary, and Yola is rendered a sort of generic English variant.

Far from celebrating Yola’s distinctions and difference from standard English, Barnes’s editorial decisions and inclusions seem to demonstrate Yola’s historical ties and similarities to the dominant English language of bygone times. What’s more, in his analysis of the sounds of the language, Barnes plays down any Flemish, French or Welsh influence and instead takes three pages to outline the similar characteristics of Yola to the ‘West English’ spoken in ‘Dorset and Somerset’ (15). As a result, the status of Barnes’s Dorset dialect is almost turned upside down, as it is put forward as a potential language of Wexford’s colonisers, rather than the language of a regional people under threat from the colonising, homogenising force of standard English.

Although a somewhat obscure and unusual book, A Glossary with Some Pieces of Verse of the Old Dialect of the English Colony in the Baronies of Forth and Bargy, County Wexford, Ireland (1867) is a text that offers a new perspective on a writer customarily associated with the defence and preservation of non-standard English. Moreover, it invites us to look more closely at the ways nineteenth-century writers attended to non-standard English variants as they crossed borders – especially the national borders within nineteenth-century Britain.